In January of 1979, my American mother sat on an airfield with her friends and family gathered in groups of twenty. In bombs fell, they were told, no more than twenty of them would be killed at a time. With the Shah (king of Iran) ousted from power, Americans were no longer welcome in Iran. Meanwhile in America, many Iranians found they were no longer welcome in the country, especially when the ensuing hostage crisis at the American embassy captured American attention in a way the actual revolution had not. I grew up on my mother's stories of Iran, the chaos that was revolution and evacuation, yes, but also her love for the Iran. For that reason, fiction dealing with the Iranian revolution has always had a dear place in my heart.

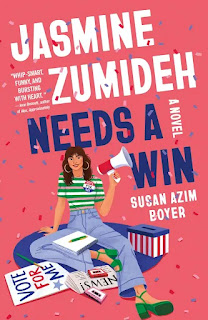

Needless to say, I'm stoked about debut author Susan Azim Boyer's forthcoming YA novel Jasmine Zumideh Nees a Win (November 2022), starring an Iranian-American teenager who finds herself experiencing anti-Iranian sentiment at school in the middle of her campaign for student body office.

|

| Susan Azim Boyer |

Erica: Though it was an important world history event, American awareness of late-seventies Iran emphasizes the hostage taking more than the revolution that led to the hostage taking in the first place. Do you ever encounter a lack of knowledge about this moment in history while describing your book to people?

Susan: Yes! This is one of the primary reasons I wrote the book: to contextualize the Iran Hostage Crisis for readers who may conflate the undemocratically elected government of Iran with Iranian people, as the media often does. And to understand that our two countries have a long, complicated relationship that dates back to the 1860s, when we forged a Friendship Treaty with Iran, through the 1950s, when the CIA thwarted an Iranian reform candidate of the people and instead re-installed an autocratic Shah (king), who was eventually overthrown during the revolution.

Erica: Follow-up question: How do you think this book may serve as an introduction for young readers who are unfamiliar with the Iranian Revolution era?

Susan: When a country like Iran has been subjected to constant negative media attention, it strips its people of their humanity. I hope my book can make Iranian Americans human, funny, and relatable to readers.

Erica: What are some favorite cultural details you were able to include in this book? You’ve mentioned on goodreads that it was fun to include some yummy foods.

Suan: Persian food, for sure! Jasmine’s Amme Minah is constantly cooking. I’ve also included pre-revolutionary Iranian history, an explanation of Persian New Year, and lots of Farsi.

Erica: Historical fiction set in recent decades rides a line between historical and contemporary. The teenagers of Jasmine’s era are in their fifties now. Teen readers have lives made different by things like technology, pop culture, and fashion. What kinds of “historical” details did you find yourself including to set the scene for a narrative in a time that’s still in living memory?

Susan: In addition to all the references to political events (Watergate, the Hostage Crisis), the book is peppered with musical references, pop culture, and the fashion of the era.

Erica: As you shared Jasmine’s story with pre-publication readers (critique partners, editors, arc readers, etc.) have you encountered any misconceptions or confusions that some readers may have about Jasmine's culture or her experience growing up as Iranian American?

Susan: The same as everyone else’s – a lack of context about events preceding the hostage crisis!

Erica: Some books with Iranian characters will explain cultural elements that may be unfamiliar to non-Iranian readers while others lean towards full immersion and leave readers to learn as they go along. For example, I recently read Firoozeh Dumas’s "It Ain’t So Awful, Falafel" and there’s a scene where the Iranian main character tells an American friend that Iranian culture places importance on hospitality and her mother has been working hard to take care of visiting relatives. I’m also reading "My Part of Her" by Javad Djavahery, which contains a similar scene where a mother works hard to take care of visiting relatives, but Javad Djavahery lets a reader pick up on that chapter's theme of hospitality on their own. To what extent did you lean towards immersion or explanation in writing Jasmine Zumideh Needs a Win?

Susan: Jasmine is learning about Iranian culture from her auntie along with the reader, so there is probably a bit more explanation.

Erica: What are some things you love about this book that you are excited for readers to experience when it releases this November?

Susan: I’m excited for them to connect with Jasmine. I hope they think it’s funny and, once disarmed by the humor, develop a fuller understanding of Iran and a deeper appreciation for its people.